The Alexander Palace is a former imperial residence near the town of Tsarskoye Selo in Russia, on a plateau about 30 miles south of Saint Petersburg. The Palace was commissioned by Empress/Tsarina Catherine II (Catherine the Great) in 1792.

|

| Current Entrance to the Czar's Wing |

|

| The Czars Formal Reception Room during Czars time |

|

| Czars Reception room 2021 |

|

| Chandelier for the Reception Room of Nicholas II |

|

| The Czars working Study during his time |

Nicholas had lived in the Alexander Palace on and off his whole life. Nicholas was born in his mother Maria's bedroom in the right wing of the palace. While he was a child his family stayed at the palace frequently and Nicholas had a personal an attachment for the palace and its' vast park. There were lots of places to visit in the park like the Imperial Farm, the kennels and the Llama House. His mother also was fond of the Alexander Palace for different reasons - she found it to be a great place for entertaining. Its' location in Tsarskoe Selo, the preferred summer resort of the St. Peterburg aristocracy, meant many potential visitors and certain invitations to balls and dinners. Maria Feodrovna loved parties and encouraged her husband to schedule long periods of time in the palace every year. The opposite of his wife, Alexander III much preferred Gatchina for its' relative isolation and the lack of social life there. As they got older Alexander and his wife spent less and less time in the Alexander Palace and more time at Gatchina.

|

| Czars Desk during his time |

|

| The divan in Nicholas's Working Study. The small chair and table at left were for the young Tsarevitch when visiting his father. |

|

| working study (by architect Roman Meltzer, 1902) |

Aside from Nicholas' father, his grandfather and great-grandfather had also all had lived at the Alexander Palace and many reminders of their lives were to be found everywhere in the palace

Over the years, as each succeeding generation of Romanovs had passed the palace on to the next as a part of the family patrimony, rooms went out of service - the personal rooms of each Tsar were left intact as memorials, preserved with all of their furnishings and intimate items untouched. This meant that portions of the palace were closed up and locked, and to the younger family members these rooms must have been exciting and mysterious places indeed. When the palace became Nicholas and Alexandra's home they spent time going through these locked up rooms and storage halls for things to use to redecorate their rooms. This must have certainly been an odd experience for Nicholas for virtually every piece of furniture and objet d'art had a history attached to it connected with some member of his family.

Nicholas was a man of conservative tastes in his surroundings - he preferred the old and familiar; rooms that were small and modest were his choice. He was embarrassed by ostentatious or trendy surroundings. Such was the environment in which he had been raised. His father had brought his children up in embarrassingly small rooms with low ceilings at Gatchina Palace and in rooms not much larger at the Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg. Alexander III made sure his children were taught to set an example, to personally do with less when it came to clothes and living quarters. While this may have made Alexander III feel good, it did nothing to meet the expectations of the people and the aristocracy - who expected their Great Tsars to live like - well, EMPERORS. As a result, people who visited the Romanovs were often shocked to see the rulers of one-sixth of the globe living more like a factory manager's family in tiny cramped rooms filled with old well worn furniture.

When then time came to refurbish the Alexander Palace for his new family Nicholas naturally chose small rooms for himself and proceeded to recreate the comfortable atmosphere in which he had grown up. While he had mostly left the plans for the 'family rooms' to his wife and the designer Meltzer, he was very specific on what he wanted in his office and private bathroom. For his office he selected old furniture from other rooms of the palace, seeming to choose the heaviest and most uncomfortable pieces for himself.

When he was finished picking out the things he wanted, as well as the carpets and fabrics, Nicholas had created for himself a dark and masculine office with the then old-fashioned look of the 1880's. The Tsar's study had dark, hand-waxed walnut panelling and a walnut firepalace set with rich dark marble. Originally the walls were papered, but - perhaps because the paper was too bright - Nicholas had the paper removed and the walls painted a dark red. The floor was covered with oriental styled wall-to-wall British-made carpet, sewn together in strips.

As his father had done before him in his study, Nicholas installed a huge divan in his office covered in oriental carpets. When he worked or returned late to the palace he would sometimes sleep there. The divan was not used much to sit on. If one were a visitor to the Tsar he would direct you to sit in a chair either in front of his desk or at a nearby table.

|

| Czars working study 2021 |

|

| The Working Study of Nicholas II © Press Service of the Tsarskoye Selo State Museum |

|

| Nicholas's Bathroom during his time |

|

| The Czar in his bathroom |

The Tsar's Bathroom had a giant heated swimming tub on a platform which also led, via a glass and wood door, to his toilet, which was a dark room hung with an assortament of pictures including a humorous cartoon of Nicholas driving a car.

The bathroom was designed in the Moorish style by Meltzer. The millwork of the room was intricately fabricated in fragrant woods. The ceiling was particularly complex. Meltzer added many interesting touches to the room including hanging glass lanterns in the shape of old mosque oil lamps. For practical reasons they were wired for electricity. He also installed magnificent antique Turkish tiles around the top of the bath. In the arcade of the tub-platform he designed elaborate patterns in Arab style.

|

| Czars Bathroom 2021 |

It was great fun for the Tsar's children, when they received permission from their father, to use his bath. A thick cord prevented falling into the bath by accident. The swimming bath was huge, it held 500 pails of water and had its' own powerful special hydraulics to rapidly pump hot water from the basement boiler up into the tub. Nicholas ordered the bath to be constructed in the palace in 1896 after seeing a similar bath on one of his estates. He used it almost everyday. A special servant was assigned to maintain the equipment below and a second servant was assigned to keep the bath spotless after every use.

Outside the tub platform, Nicholas installed the chinning bar, seen in the photograph, in 1916. The Tsar was passionate about exercise and also had a similar chinning bar in his train. He also had weights in his bathroom for working out. The Tsar was somewhat self concious about his small size and worked hard to build himself up. As Anna Vyrubova relates in her later memoirs:

"...To tell the truth, the Tsar was rather weak and lean. When he was sitting it seemed he was well-built but in fact he was not even of medium height because of his short legs. Nevertheless, he managed to harden his organism by sports and physical exercise in fresh air and develop physical strength....

Nicholas II was Alexander's III elder son. Alexander III loved his son (who in his turn adored his father) whose physical development left much to be desired. Alexander III himself was almost a giant - he could tear a pack of cards into two halves, crush a piece of silver as if it were a rusk, straighten a horse-shoe, tie a poker in a knot, etc."

On the back wall, by the left hand side of the door to the Working Study, was a collection of ikons and hanging Easter eggs. To the right was draped an embroidered cloth with a double eagle, probably the work of Alexandra or one of the girls.

Nicholas kept a large collection of Fabergé cigarette cases on the table in front of the window. He put up a display of gifts and small objects from his children in the bathroom. These included porcelain penguins and dancing girls. A floral watercolor painted by his daughter, Marie, and dated May 1917, hung on the door from the bathroom to the Working Study.

The Tsar had a parrot which he kept in his bathroom. The parrot's name was Popov and Nicholas had inherited Popov from his father.

|

| The New Study during Nichols's time. This room would be where the Czar received people |

|

| The New Study 2021 |

|

| The Small Library was used by the Imperial Family as a Dining Room |

|

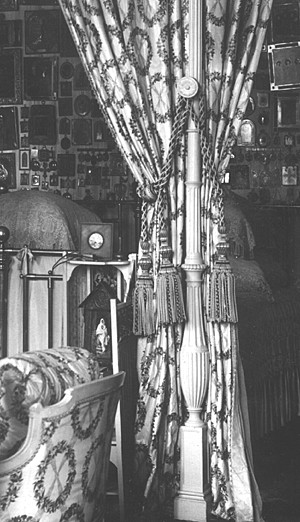

| The Empress's Drawing Room during her time |

|

| Colour autochrome of the Corner Reception Room, taken in 1917 |

Alexandra's Formal Reception Room was one of the sunniest rooms in the palace and the largest of the personal rooms of the Imperial family. It connected to one of the palace libraries and was situated in the far right corner of the palace. Seven big windows looked out from the Reception Room onto the Alexander Park. The walls were covered with white artificial marble and topped by a beautifully molded entablature whose crispness and clean classical design is the mark of the work of the architect Quarenghi. This room preserved the austere late 18th century style which Catherine the Great had intended for her grandson's palace. It is possible that some of the furnishings of this room were a part of its original decoration.

The snowy whiteness of the room was set off by heavy, cranberry-colored curtains on the windows, which had inner drapery made of thin lace. The floor was made of a dark gold parquet. In the center of the room hung a beautiful crystal chandelier with a ruby-red glass center in the Russian manner. Rudy-red blown glass is very difficult to make - the red color is obtained by adding gold to the molten glass before it is blown into its delicate shapes by the glassmaker. This chandelier dates from the epoch of Catherine the Great and was most probably original to the room.

The furniture included some of the finest in the palace, including a roll top desk, which contained a musical mechanism, by famed German cabinetmaker, David Roentgen. It dated from the time the palace was built ands may have been part of Catherine's wedding gift to Alexander and Elizabeth. This piece was Alexandra's formal writing desk and it was considered one of the most valuable works of art in the palace. After the revolution it was evacuated to Moscow. When it returned to Petersburg it was sent to Hermitage, where it stands today. In its' place museum workers substituted another desk by Roentgen, one of a matching pair which were found in the palace. These may have been the working desks of Alexander and his young wife Elizabeth.

|

| The Maple Room was used as a Family Room of Sorts by the Imperial Family |

Alexandra had originally been a Princess of Hesse and was raised in both the Hessian capital of Darmstadt and in England with her Grandmother, Queen Victoria. The Empress's brother Ernst-Ludwig became Grand Duke of Hesse on the death of their father. Ernst-Ludwig was interested in all of the arts and attempted to make his Darmstadt a global center for the development of modern art. The Grand Duke established the Darmstadt "Artist's Colony" where the decorative and building arts were broguht together in a world's fair type of environment - but without blatant commercialism. The greatest artists of the time took part in the exhibitions, including Peter Behrens and other leaders in the development of the then "modern style' which was called Jugendstil in Germanic countries and Art Noveau in the USA, England and France. In Russia it was called the "Style Moderne". This movement found fertile soil of Darmstadt from the encouragement of the Grand Duke and a splendid complex of buildings and pavillions at the Artist's Colony. The exhibitions there included actual model homes in Jugendstil style, in which everything right down to the silverware was designed by famous artists like Behrens. Nicholas and Alexandra visited these exhibitions and their visits were the occasion of gala receptions by the Hessians and much free publicity for the exhibitions. Alexandra liked modern things and she appreciated what she saw as they were conducted through the exhibition halls and around the model houses. She was very proud of her brother's accomplishment and the role of her native land in the encouragement of modern art. The Empress bought many things at the Artist's Colony - vases, material, furniture and such - although Nicholas himself detested the Art Nouveau style - especially in its' more extreme and austere manifestations.

|

| Pushkin, Tsarskoe Selo. Alexander Palace interior – Maple Room, by architect Roman Meltzer |

Ernst-Ludwig was a frequent visitor to the Alexander Palace and he must have certainly given his sister a great deal of advice about decorating and entertaining. Alexandra admired her brother and was very close to him in temperment and inclination. After her husband, he was probably her closest and most trusted friend and confidente in the world. Ernst-Ludwig was one of the few people to whom she listened and she accepted advice from him. While accepting of Ernst's counsel, she bore a silent and grudging resistance to the recommendations of her much older sisters, which she often found to be condesending. Her sister Elizabeth had spear-headed the redesign of the rooms of the Winter Palace in 1894-95 and the Empress always felt they were more her sister's style then her own. Nicholas and Alexandra made decisions about fabrics and rugs, but the layout and styles selected were the result of Elizabeth's ideas working directly with Roman Meltzer, the decorator.

When Alexandra told Ernst-Ludwig in 1902 that she and the Emperor planned to expand their living space at the Alexander Palace and that she and Meltzer wanted to design the space in the Jugendstil style he must have felt pleasantly impressed and ready to assist. The plans were for two large rooms to be built on the main floor with more children's rooms above. One of the main rooms would be a comfortable sitting room for the Empress, and it came to be called the Maple Room, because of the lavish use of Maple wood througout the space.

The Maple Room was a big, spacious and charming interior - full of light - which was probably the finest Art Nouveau interior in Russia. The walls were painted a warm dusty pink. Ornamenting the walls were carved and moulded white-plaster trellises of German cabbage roses which climbed and entwined themselves about a pale green circle set in the center of a high ceiling. Around the room a high, overhanging curved cornice concealed hidden electric lamps which cast soft indirect reflected light over the room from the white ceiling; one of the earliest uses of what is now a commonplace lighting technique and was quite daring in its time.

|

| Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia with her beloved lilacs in the Maple Room in the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo. |

|

| The uniquely-designed cornice and coved ceiling with the bas-relief of delicate German cabbage roses |

The carved plaster cabbage roses were skillfully duplicated in delicately carved wood on a great maplewood balcony which sailed across the entire room from one side to another. The balcony was curved at the top and was inset with leaded glass panels. Lacy bronze lamps with art glass shades hung like bats from its' supports. A staircase with sinuous carved railings lead from the right corner to the top of the balcony from which direct access to a mezzanine level over the corridor connected to Nicholas's New Study.

|

| 2021 Entrance to the Maple Room |

The maplewood used in the construction was a special variety which, it was said, required seven years immersion in water in order to be worked and shaped in the serpentine fashion of Art Nouveau. Maplewood was the preferred wood of many art nouveau furniture artists. Its' hard grain was a challange to carve, but the wood took on a deep sensual glow when polished - shining like dull matte gold. The wood was also very strong and thin supports could be produced which were quite durable. Large quanities of it were used in this room for the furnishings and it was of course the source of the room's name.

Beneath the balcony were two cosy sitting areas separated by a fireplace set with ceramic tiles. The Empress had an Art Nouveau chaise lounge under the balcony nearest the window, directly behind huge planters where fragrant flowers in pots were situated. On the opposite side beneath the balcony was a sitting area for her children, where they could work and play while the Empress read or worked at needlework nearby. Above the banquettes were shelves for small vases and collectables.

The centerpiece of the room was a great built-in maplewood cabinet in the left corner closest to the Pallisander Room. In the original design for the room this space was designed for a corner heating stove. It was Alexandra's idea to eliminate the stove - which was useless given that central heat was now used in this part of the palace - and she had a part in the design of the cabinet. This was the place where the Empress kept many of her famous Fabergé eggs. The cabinet was rather high up and somewhat hard to get at - thus a safe place to store delicate items. It rose above a curved cozy corner covered in Darmstadt fabrics - this which was a favorite place for family teas. Along the backs of the curved sofa was a wide ledge, where many of the Empress's favorite things were displayed. Here, in a glass and silver cabinet placed so that light shown through it, Alexandra kept a collection of animals carved from hardstones. Alongside the cabinet were vases of flowers, bronzes and other small things.

|

| Fireplace in Mezzanine |

|

| Corner sitting are lower area by fireplace |

|

| Palisander room in the Alexander Palace was a Sitting room made of Rose Wood in an English Style to reflect the Empress's youth |

|

| Palisander Room, Autochrome color photograph plate |

Before the construction of the Maple Room this was the primary Sitting Room of the Imperial apartments. Nicholas describes this room as the green "Chippendale Room" in his early diaries. At the time the wooden corner fireplace in the room, with its cornices and many shelves was seen as a "Chippendale" piece. Nicholas and Alexandra liked this room and during their fist years in the palace it was one of their favorite cozy spots to be alone.

The walls were hung with pale straw-green silk and the floor was laid with British carpet woven with a diamond pattern with a wreath motive in shades of soft purples.

On the screen in front of the fireplace are watercolors of Alexandra's childhood homes in Hesse. The fireplace has a grass screen in front of it and it's shelves contain pieces of Danish porcelain from the Royal Copenhagen Factory. In the center of the mantle is an Art Nouveau clock with pieces of Gallé and Russian art glass on either side.

From the center of the room hangs a large gilt-bronze and crystal chandelier in the Empire style.

|

| The Rosewood Drawing Room in 1917. Autochromes of Andrei Andreyevich Zeest are made in June-August 1917. |

|

| The Palisander Room during remodel |

Nicholas and Alexandra personally chose the paintings to be hung in this room and they intended their selection to indicate their own personal tastes. The two on either side of the fireplace were new paintings purchased by the Empress specially for this room. The one on the left is "The Annunciation" a work in Art Nouveau style. The painting on the right is a "Madonna and Child" by Paul Thuman. Alexandra also brought a painting of her father by Plueskow which was done in 1894, and a painting of her mother, Princess Alice of Great Britain and Ireland which was a copy painted by Kobervein. The largest painting in the room was a huge canvas of Romrod Castle in Hesse. There were also works by famous Russian artists and a watercolor by the English painter Sir Edward Poynter, which was purchased by Nicholas on a trip to Great Britain.

Intimate guests and visitors to whom the Tsar or Tsarina wanted to show special favor were invited to this room, which was a part of their private chambers. Warm, highly polished rosewood panelled the room. Meltzer custom designed furniture for the room which was crafted in his family's workshops in St. Petersburg. The material chosen for the furniture - rosewood inlaid with delicate motifs in rare, contrasting woods - matches the panelling. The style of the room is typical of English-style interiors of the time and is similar to one shown by Bing in his Paris Exhibition of the same year. This rooms was published and widely admired.

English-style interiors were characterized by the use of high wood wainscotting and contrasting textures in materials used to decorate the room. Here in Meltzer's interpretation he takes the older English Arts and Crafts Movement and blends it with subtle elements of the then emerging Art Nouveau movement. This can be best seen in the proportions of the furniture and use of new decorative motifs. Modern sensibilities can also be seen the plushness of the upholstered furniture, which were more comfortable than stuffed furniture of earlier decades. The fabrics used in this room were heavy tapestry weaves in muted Arts and Crafts colours. The British carpet matched the floor covering of the Mauve Room, although it was in a different color. The silk wall covering is a yellowish-green. The Pallisander Room could easily have worked as a dining room as well as a sitting room and was sometimes used for that purpose. This was often the site for the family's daily tea.

|

| Mauve Boudoir during the time of Empress Alexandra This was her personal sitting room and where she spent most of her time. |

Alexandra was only 22 when she moved into the Alexander Palace. Until then she had felt like something of a vagabond and perennial guest without a real 'home' of her own. She was shuttled between Darmstadt and her grandmother Queen Victoria's homes at Balmoral in Scotland and Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Even the Darmstadt palaces in which she lived belonged first to her father and then to her brother and his wife, not to her. When she was a teenager it was understood she would make her home elsewhere with her future husband. Should no husband arrive to rescue her Alexandra's fate would have been to retreat as a spinster to an obscure suite in one of family's palaces or a cottage on some Royal estate - relying on the charity of others.

When Alexandra came to Russia she was involved for the first time in creating her own living spaces. She was inexperienced and most of what she knew about decorating came from magazines and the advice she had received over the years from of her English Grandmother and observations of Victoria's old-fashioned, sentimental style of decorating which dominated a century. Although Alexandra's tastes were conventional and hesitant she made many suggestions to the decorator, Roman Meltzer about placement of furniture, colors and fabrics. Her objective was to create a bright and cozy environment for her husband and future family. She wanted a room where Nicholas could come and unburden himself from the affairs of government - a sanctuary where they could be together, safe and alone. As Alexandra worked with Meltzer price was never discussed. This was considered undignified. Not knowing prices was disconcerting to Alexandra, who was used to very carefully managing her money like any good German "hausfrau". She wanted to keep costs down while everyone else involved seemed not to care at all about cost, focusing instead on obtaining the finest quality materials available. The total budget for the redecoration of the Alexander Palace would have astounded the young Tsaritsa, if she had been brave enough to enquire what it all had cost.

The Mauve "Boudoir" was Alexandra's favorite room and for 20 years it was the center of her family's life in the palace. At the time it was the most celebrated room in Russia and the subject of much gossip as to the events that were supposed to have taken place there. Even today it remains a room of mystery and it is the room of the palace which interests the public the most. The room was also much derided for its' style and family atmosphere by elite society of the time. Elegant Petersburg thought proper Romanov Empresses should live semi-publically in splendid rooms graciously decorated in the latest style with fine art and sophisticated furnishings.

For 21 years - though changes in style and decorating came and went, Alexandra resisted any suggestions to remodel this room. It held too many memories for her and she was determined to keep it just as it had been when she was married. This meant the Mauve Room, which was considered lovely, modern and very chic in 1896, was hopelessly outdated, quaintly old-fashioned and something of an inside family joke by 1917. The opal tones, art glass and delicate furniture had long since gone out of style in favor of bolder effects.

|

| The Mauve Boudoir 2021 |

|

| the restored writing table of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna |

The Romanov Tercentenary Egg is made of gold, silver, rose-cut and portrait diamonds, turquoise, purpurine, rock crystal, Vitreous enamel and watercolor painting on ivory. It is 190 mm in height and 78 mm in diameter. The egg celebrates the Tercentenary of the Romanov Dynasty, the three hundred years of Romanov rule from 1613 to 1913. The outside contains eighteen portraits of the Romanov Tsars of Russia. The egg is decorated in a chased gold pattern with double-headed eagles as well as past and present Romanov crowns which frame the portraits of the Tsars. Each miniature portrait, painted by miniaturist Vassily Zuiev, is on ivory and is bordered by rose-cut diamonds. The inside of the egg is opalescent white enamel. The egg sits on a pedestal that represents the Imperial double-headed eagle in gold, with three talons holding the Imperial scepter, orb and Romanov sword. The pedestal is supported by a purpurine base that represents the Russian Imperial shield.

Among the 18 rulers represented are Michael Fyodorovich, the first of the Romanov Dynasty in 1613, as well as Peter the Great (1682–1725), Catherine the Great (1762–1796), and Nicholas II himself as the final Tsar in 1913.

14 April 1913 (O.S.) Presented to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, a gift from Nicholas II at a cost of 21,300 rubles.

1913-1916. Housed in Alexandra Feodorovna’s Mauve Boudoir at the Alexander Palace,Tsarskoe Selo.

The Fifteenth Anniversary Egg is an Imperial Fabergé egg, one of a series of fifty-two jewelled enameled Easter eggs made under the supervision of Peter Carl Fabergé for the Russian Imperial family.

It was an Easter 1911 gift for Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia from her husband Tsar Nicholas II of Russia,who had a standing order of two Fabergé Easter eggs every year, one for his mother and one for his wife.

Its 1911 counterpart presented to the Dowager Empress is the Bay Tree Egg.

The egg is made of gold, green and white enamel, decorated with diamonds and rock crystal. The surface is divided into eighteen panels set with 16 miniatures.

The egg's design commemorates the fifteenth anniversary of the Coronation of Nicholas II on 26 May 1896.

There is no "surprise" in the egg— contrary to the Tsar's explicit instructions with regard to these eggs and without explanation, apparently none was ever made.

10 April 1911 (O.S.) Presented to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, a gift from Nicholas II at a cost of cost 16,600 rubles.It was between 1911-1916 housed in Alexandra Feodorovna’s Mauve Boudoir in the Alexander Palace,Tsarskoe Selo.

|

| Alexandra feodronova in the mauve boudoir of the alexandra palace |

|

| The Czar reading the newspaper in the Mauve Boudoir |

|

| Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia in the Mauve Boudoir at the Alexander Palace,Tsarskoe Selo. |

|

| The Tsarevich Alexie seated, Grand Duchess Maria, Grand Duchess Tatiana, Grand Duchess Olga, and Grand Duchess Anastasia. |

|

| Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia with her youngest daughter the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova of Russia in the Mauve Boudoir at the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo. |

|

| Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanov in her mother´s Mauve boudoir 1906. |

|

| Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova of Russia (1895-1918) with her brother, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich Romanov of Russia (1904-1918), in their mother’s Mauve Boudoir, |

|

| Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana Nikolaevna Romanova of Russia in the Mauve Boudoir at the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo. |

|

| The Empress with all four Grand Duchesses in the Mauve Boudoir |

|

| Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna Romanova of Russia in the Mauve Boudoir at the Alexander Palace, Tsarskoe Selo. |

|

| photograph of Grand Duchesses Maria and Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia |

The Imperial bedroom was the most private and intimate room of the palace. It could only be entered after passing through the Pallisander Room and the Mauve Room.

When Alexandra first saw this room, it had been untouched for more than twenty years. When their occupants were away, palace rooms were shut up with the furniture in canvas covers and the paintings covered in sheets. Small things were packed away in drawers or sent to storage. Sometimes the windows were covered with heavy shutters. Servants were assigned to dust and clean these rooms periodically but most of the time the rooms remained locked with the keys in the control of the palace marshal. Alexandra may have been told that this room and the mauve room next door had connections to her family. In a strange twist of fate Alexandra's mother Alice had visited these rooms years before when she attended the wedding of her brother, the Duke. The room had been a part of a honeymoon suite that Alexander II had established in the palace for his daughter Maria when she married Alfred, Queen Victoria's son and the Duke of Edinburgh.

After seeing the room and discussing it with her husband and the decorator Meltzer it was decided to leave this room much as it was. Alexandra liked the room and it seemed pointless to her to waste money - and time - on a complete redecoration when much of the furniture would still work. So, the 1870's furniture, which was made in Russia, was reused, although it was painted in a heavy coat of white enamel to lighten and make it cheerier. A great columned arcade which traversted the room from one side to another was also painted white, while the fabrics and floor coverings were replaced.

Alexandra selected a shiny chintz print for the walls, upholstry and curtains. The pattern was of pink ribbons entwined with green wreaths set with flowers on a white background. The effect of using the same fabric for an entire room had been used earlier in Russia at Gatchina Palace, however the effect here at the Alexander Palace was greater due to the colors and the effect of the trellis pattern. Kuchumov, the former director of the palace museum, said that the fabric gave the room a funereal feel, with the beds placed like a bier in front of the ikon wall. This was certainly not the Empress's intention. For her the room had the look of a bright English garden or a tent decorated for a June wedding.

The bed faced the window, behind it were ikons and religious items which were hung on cords. Many of the ikons were ancient and valuable. The centerpiece was a large ikon of the Feodorovsky Mother of God - an ancient copy of the ikon used to bless the first Romanov Tsar when he accepted the throne. Other ikons were encased in silver covers (oklads) and covered in enamel and jewels; some were products of the workshops of famed jeweller, Fabergé and the famous Moscow silversmiths Khlebnikov and Ovchinnikov.

Most of these ikons were gifts to the Imperial family from imortant monasteries, churches and religious organizations around the country and even from abroad. The backs of many of the ikons were inscribed with the subject matter, the giver and the date. When Nicholas and Alexandra lived in the palace there were fewer ikons than are seen in this photo taken before 1941. In Soviet times, when the palace was a museum, museum workers moved other ikons belonging to the family here from the children's rooms that were shut down by the government and turned over to Secret Police officers as private trysting rooms where they met their mistresses. Other ikons came from palaces where Romanov rooms were destroyed - such as the Winter Palace. In 1941 there were more than 300 ikons on the walls. There were two ikon lamps on the wall in the shape of doves. During the Imperial period, they were kept continuously lit with rose oil. Over the 21 years the scent impregnanted the fabric and very walls of the room. They were never extinguished until August 1, 1917, the day the Imperial Family went into exile. Twenty years after the Romanovs had been exiled from the palace visitors said the scent of roses was still overpowering.

Alexandra had problems sleeping and she was up much of the night - probably due to chronic worry. During the night she would nibble on fruit and crackers which was set out for her every night on a side table. They were awakened each morning by a servant at the door to the Mauve Room; on the other side a lackey would pound on the door with a silver mallet three times, a tradition started in the reign of Catherine the Great which continued up until the revolution. Nicholas was often up long before this - putting on his robe and crossing the corridor to his bathroom and dressing room. Alexandra was frequently late to rise. When she got up her ill health often meant that she went no further than the sofa in front of the bed.

In 1941 the German Nazi Army and their Spanish allies occupied the palace. During their stay they made a sensational discovery. Where the arcade meets the bedroom wall they found a secret safe concealed beneath the fabric. During the 25 years the Palace had been a museum no one had found this secret hiding place. This is amazing considering the repeated numerous searches in the palace for Romanov treasures conducted by the Soviet Government over the years. Everyday the palace was open, thousands of people walked just a few feet from the secret safe, yet no one suspected its existence. Yet, the invading German army seemed to have known it was there. When the Soviet Army re-took the Palace they found the strong box in the wall, but it had been emptied. What did the Germans find in the vault? Was this a secret hiding place for Romanov jewels? No one has yet revealed the secret.

The Dressing Room opened off of the Imperial bedroom. Every morning the Empress would rise to find her clothes set out by her maids and waiting for her in this room. The maids had private access to the room via an ashwood staircase from their work room on the mezzanine level, where the Empress's clothes were stored and prepared. The staircase lead to the toilet which opened off of the dressing room. The Grand Duchesses used this internal staircase which ran from their rooms via the maid's mezzanine and a second bathroom to their mother's room.

Alexandra selected her clothes for the week in advance based on the activities she had on her calendar and her personal preference. She would meet with her maids and go over this selection. Each day she would receive a written recap of what was planned for the following day and she would then make final instructions for her wardrobe. Sometimes she would be undecided about what she wanted to wear and would request several outfits to be made ready for her to select from.

After bathing, Alexandra dressed herself. She would change her clothes several times a day, dressing more casually for the morning, and then more formally for luncheon and tea. The Empress was attired regally in expensive evening dresses for dinner, set off with magnificent jewels, even when she and Nicholas dined alone. After dinner Nicholas returned to work and the Imperial couple rejoined for a late evening tea, which was often served in Nicholas's Working Study. Following this the Empress would return to her rooms to prepare for bed. Her dressing gown and bedclothes would be waiting for her in the dressing room.

Like clockwork, the clothes she had selected for the day would appear in this room at the proper time. The maids were expected to do all of this as quietly as possible and promptly on schedule. When Alexandra entered her dressing room she expected the maids to be gone and everything waiting as she had instructed. On the right-hand wall was a wall phone for her to speak with her maids upstairs if something wasn't quite right or if she needed some accessory.

The dressing room fireplace; above the fireplace is a large picture of Alexandra's father, the Grand Duke of Hesse.

The equipment for maintaining the Empress' clothes was extremely up-to-date. The maids used electric irons to press the Empress' clothes and stored her furs, fine shawls, gloves, evening wear and other clothes in big oak closets protected against damp and moths. They were provided everthing they needed to ensure Alexandra looked her best at all times. The Tsar and Tsarina's clothes were cleaned in the laundry of the Anichkov Palace of St. Petersburg. They were bundled in hampers and special bags for transport. The clothes of the children were washed in electric washing machines in the Imperial laundry of Tsarskoe Selo.

The dressing room had simple furniture which was painted ivory and covered with cotton chintz fabric. The arm chair in the picture at the top has a fish pillow- another embroidery by Alexandra or one of her daughters. The floor was covered by a fine sewn English carpet. The door to the Empress' toilet and bath is on the left. The room has a fireplace, it was important that this room be kept warm. On the right wall was a thermometer with a buzzer to the heating rooms down in the basement. Alexandra would signal the attendant there if the room was too warm or cold. Above the fireplace were original watercolors showing the baptisms of Marie and Anastasia, they were artists original designs for popular prints commemorating these events.

|

| The Dressing Rooms as it appears in 2021. This room is not going to be restored to the 1895 configuration as the ceiling uncovered is rare. |

The dressing room, toilet, mezzanine workroom and bathroom were all constructed in 1895 from one room. After the war these rooms were ruthlessly destroyed by the Soviets - in the process of ripping them out a beautiful neoclassical painted ceiling was discovered and restored by the celbrated Soviet restorationist Treskin, who also restored Pavlosk Palace.

No comments:

Post a Comment