The Alexander Palace is a former imperial residence near the town of Tsarskoye Selo in Russia, on a plateau about 30 miles south of Saint Petersburg. The Palace was commissioned by Empress/Tsarina Catherine II (Catherine the Great) in 1792.

Due to the privacy it offered, when officially resident in St Petersburg, the Alexander Palace was the preferred residence of the last Russian Emperor, Nicholas II and his family. Its safety and seclusion compared favorably to the Winter Palace during the years immediately prior to the Russian Revolution. In 1917, the palace became the family’s initial place of imprisonment after the first of two Russian Revolutions in February which overthrew the Romanov during World War I. The Alexander Palace is situated in the Alexander Park, not far from the Catherine Park and the larger, more elaborate Catherine Palace. As of 2020 the Alexander Palace is undergoing renovation as a state museum housing relics of the former imperial dynasty.

|

| Empress-Tsarina Catherine II (Catherine the Great) of Russia by artist Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder. |

The Alexander Palace was constructed in the Imperial retreat, near the town of Tsarskoe Selo, 30 miles south of the imperial capital city of St. Petersburg. It was commissioned by Empress/Tsarina Catherine II (Catherine the Great) (1729–1796, reigned 1762–1796), built nearby the earlier Catherine Palace for her favorite grandson, Grand Duke Alexander Pavlovich, the future emperor (tsar/czar) Alexander I of Russia (1777–1825, reigned 1801–1825), on the occasion of his 1793 marriage to Grand Duchess Elizaveta Alexeievna, born Princess Luise Marie Augusta of Baden.

The Neoclassical edifice was planned by Giacomo Quarenghi and built between 1792 and 1796. It was agreed that the architect had excelled himself in creating a masterpiece. In 1821, a quarter of a century later, the architect's son wrote:

An elegant building which looks over the beautiful new garden ... in Tsarskoe Selo, was designed and built by my father at the request of Catherine II, as a summer residence for the young Grand Duke Alexander, our present sovereign. In keeping with the august status of the person for whom the Palace was conceived, the architect shaped it with greatest simplicity, combining both functionality with beauty. Its dignified façade, harmonic proportions, and moderate ornamentation ... are also manifested in its interiors ..., without compromising comfort in striving for magnificence and elegance.

|

| Equestrian portrait of Emperor (Tsar Czar) Alexander I (1777–1825, reigned 1801–1825), in 1812 by Franz Krüger |

Alexander used the palace as a summer residence through the remainder of his grandmother's and his father, Paul's, reign. When he became emperor, however, he chose to reside in the much larger nearby Catherine Palace.

Enfilade

The Great Library /Великая библиотека

This room was originally two stories with a hanging balcony. This two story room was impressive, but it cut the left hand wing off from the rest of the palace. During the reign of Nicholas I it was altered and the ceiling was lowered with new rooms inserted above. Nicholas I made many changes to the Alexander Palace. It was his family's home in Tsarskoe Selo and he lived there for extended periods of time every year . He took great interest in the palace and its grounds. Nicholas had his own flower beds outside the Formal Reception Room where he planted favorite bulbs and bedding plants with his own hands.

There were many bronze statuettes and ship models in the room. The collection of books included part of the Private Library of Paul I, which was sent here after his death.

In the reign of the last Tsar, Nicholas II had two, full time librarians on his staff to look after the collection of the Alexander Palace, which was a unique collection of both rare and historical books. The collection was broad and reflected the personal tastes of succeeding generations of Romanovs who lived in the palace. Serious scientific volumes sat alongside plays, albums of watercolors, early Orthodox theological works and historical books. Many books were splendid editions-deluxe covered in expensive hand tooled leathers with gilt and silver fittings. The size of some of these volumes was amazing and they required two people to lift onto tables and turn the pages. The palace collection also included rare magazines and pamphlets from the late 18th through the early 20th centuries which document everyday life and changing tastes in daily life, dress and fashion. The libraries included early fashion 'magazines', which documented the history of style during the first decades of the 1800's and these were a source of amusement to Aleksandra and her daughters in the last years of the monarchy. They had been collected by successive reigns of Tsaritsas and their daughters - all carefully cataloged and store away by dutiful Imperial librarians. After the revolution a part of the library's collection was sold by the Soviet Government, which was looking for convertable currency to finance Communist parties in foreign countries. A large number of these books now reside at Harvard University and in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. The New York Public Library also cherishes a collection of Imperial books from the Alexander Palace.

During the Second World War the curators of the Palace-Museum were forced to leave most of the library behind. There were not enough packing materials, crates, nor transport or time to pack the library in advance of the German troops. In the vain hope that they might be overlooked by the Germans, the books were stacked in out-of-the-way basement rooms and inconspicuous closets. Unfortunately, art specialists and professional appraisers travelled with the German Army and they poured over the Alexander Palace treasures, picking out choice pieces for Nazi officers and officials back home. What was left over was picked at by soldiers, who sent books and art objects back home to their families. As a result thousands of volumes from the library were stolen or destroyed by the Germans and their Spanish allies. Most of the stolen books and art objects still remain in private hands in the West and have not been returned. Almost no effort has been made in recent times to locate and return them to Russia.

The Marble Mountain Hall

The Mountain Hall received its name during the reign of Nicholas I when a great slide was installed in this hall which took up about half the room. In Russia slides are called 'Mountains' - hence the hall's name. Prior to the installation of the slide, which effectively obscured most of the room, the Mountain Hall room was one of the loveliest rooms in the palace. Its walls were encrusted with artificial marble of exquisite color and delicate veining, which gave the room a cold, glassy luster.

For children the slide would have been, of course, the most interesting object in the hall. It was ordered for the children of Nicholas I. His family spent long periods of time here. He had a large family and a large part of the palace was given over to family activities. This continued to be true in the reign of his son, Alexander II, who shared his father's love of the palace and who also had a large family. The slide was used right up until the revolution by generations of Romanov children and was used by little Aleksey and his friends until the family's exile to Siberia in August 1917.

Alongside the slide there was an organ which played circus-type tunes while the Imperial children frolicked on the slide. Parrot cages scattered around the hall, including a big one on the top of the slide where for birds who were trained to sing and screech on cue when the organ was played. This racket added to the fun for children using the slide. The surface of the slide was highly polished wood. Pieces of fabric and carpet were used to slide down the slick surface. It is surprising that the slide was placed in the midst of fragile works of art, porcelain and delicate glass candelabra.

It must have been quite a chore for the servants to safeguard the treasures while the Romanov children were darting about the room at play. In the picture above one can also see Aleksey's miniature Mercedes, which was a gift from his parents on his birthday. This was one of his favorite toys and it was brought here after the revolution. Visitors to the palace commended frequently on this car and its sad association with the murdered Tsarevich. Exhibitions of court costumes were also held here during the years the palace was open as a museum. Suzanne Massie in her book, Pavlovsk, Life of a Russian Palace, describes the last of these exhibitions just before the Second World War.

|

| Marble or Mountain Hall © Press Service of the Tsarskoye Selo State Museum |

The Portrait Hall

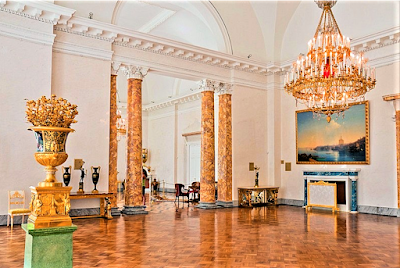

The Portrait Hall was one segment of the great three-part hall which made up the central core of the palace. One one side a door led from the Portrait Hall into the Mountain Hall. On the opposite side it opened through a great arch and arcade of columns into the Semi-circular hall. The columns were made of artificial painted golden Sienna marble with Ionic capitals. The walls were covered in white scagiola - an artificial marble surface made of ground pure white alabaster. The soaring vaults of the room were painted a simple and pristine white white set off the massive chandelier from the time of Catherine the Great which hung from the center. Huge window's opening onto the park let in massive shafts of light. The floors were set with plain parquet in a diamond pattern, which was kept so highly polished it was a hazard to anyone walking on it. Servants had to wear shoes with special soles to prevent slipping and falling on the slick parquet. Numerous carpets from France, Russia and the Near East were strewn across the floor.

|

| This painting was a wedding gift to Catherine's grandson, Alexander I, on the occasion of her presentation of the Alexander Palace to him in 1796. |

|

| A mammoth painting of Nicholas I on horseback dominates this wall of the Portrait Hall. |

|

| A view from the Portrait Hall into the Semi-circular hall and from there into the Billiard Hall. |

The Portrait Hall was used frequently for entertaining and the traditional Russian "Zakuska" course - hors d'oeuvres as a prelude to dinner - was often served in this room to standing guests with drinks served by liveried servants. The main dinner itself would be served in the adjoining Semi-circular Hall. The Russian Zakuska is an elaborate and large hors d'oeuvres buffet of cold meats and poultry, smoked fish, cheeses, pates, breads, dozens of salads, and of course, lavish amounts of caviar. Typically, it would have been acommpanied by large quanitites of ice cold vodka, or French Champagne.

An image above shows a view into the Semi-circular Hall and shows the three giant chandeliers and the beautiful central space of the Palace. The chandeliers are from the reign of Catherine and are the originals probably designed by Quarenghi. They had a third lower tier added sometime in the late 19th century and were electrified in 1895. On the far left is part of a large painting of Catherine the Great. Beneath it is one of a pair of magnificent lapis, carnelian and jasper tables which Alexandra had brought to the palace in 1902. Unfortunately neither of these can be seen well in this photograph. These tables are now in the recently restored Arabesque Hall of the Catherine Palace.

Because of the bright light in this room and its impressive furnishings, the Portrait Hall was often used for formal photographs of the last Tsar and his family. None of the photographs shown here include the big palm trees from the Imperial Greenhouses which would have decorated the room prior to 1917.

|

| The Enfilade in 1917. Autochromes of Andrei Andreyevich Zeest are made in June-August 1917

|

|

| The Portrait Hall in 1917. Autochromes of Andrei Andreyevich Zeest are made in June-August 1917

|

|

| The Portrait Hall in 1917. Autochromes of Andrei Andreyevich Zeest are made in June-August 1917

|

|

| Portrait of Grand Prince Alexander Nikolayevich by Franz Kruger |

|

| Portrait of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich Botman - (1848) |

|

| Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia by Franz Kruger (1847) |

|

| Franz Kruger Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich in the cornet uniform of the Leib-Guardian cavalry-grenadier regiment. The Tsarskoe Selo Palace-Museum |

|

| Alexander I of Russia by G.Dawe |

The Semi-Circular Hall

The Semi-Circular Hall is one of the most famous rooms of the Alexander Palace and is the center of the formal ensemble of parade halls. It remains essentially as Quarenghi designed it, with the only major change being the replacement of a pair of Russian stoves on either side of the entrance with marble fireplaces, during the reign of Nicholas I. The walls are covered, in the Russian style, with smooth, white artificial marble. The central doors of the apse open out onto a terrace overlooking the Alexander Gardens. It was through these doors that the Imperial Family left the palace for the last time on August 1, 1917.

The spaciousness of the Semi-circular Hall, which opens through broad, columned arches into the Portrait and Billiard Halls, is one of the most ambitious spaces in any Russian palace. The three rooms resemble the central hall of a Roman bath which may have been Quarenghi's intent. No other Imperial Russia palace has quite the same restrained, airy, yet opulent mood in its public spaces. It may reflect Catherine the Great's intention to mirror her ideal vision of what her grandson Alexander I could and should become as Tsar - a masculine, enlightened, and cultured ruler - much like herself.

View through the doors onto the garden terrace of the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. The Imperial family exited through these doors on their last morning in the palace before their Siberian exile in 1917.

Entrance door to the Semi-circular Hall. This picture was taken when the palace was a museum after the revolution and a display case blocks it. The fireplaces on both sides of the door were originally traditional tall Russian stoves. They were replaced by these marble ones by Nicholas I.

|

| The Semi-circle Hall 2010 |

Semi-Circular Hall

This is the center of the gala suite of rooms. This chamber had the least number of changes in the course of history and looks almost the same as Quarenghi made it. The walls of the room, like in the other two, are faced with shiny artificial marble. The hall gets its name from the apse, which is semi-circular and the central door leads onto the terrace overlooking the garden. Through these doors on August 1, 1917, the “Former Tsar’s Family” has left Alexander Palace forever. The leader of the Provisional government Alexander Kerensky exiled them to the city of Tobolsk in Siberia.

The Marble Drawing Room/Billiard Hall

All three rooms, the Portrait, Semi Circular and Billiard/Marble Halls communicate by wide arched columned arcades. They can be experienced as one vast hall. The Billiard Hall was also called the Marble Hall. During the reign of Nicholas I billiards became a very popular pastime for men and women in noble homes. The billiard tables and horsehair-stuffed furniture in the this hall were removed during the reign of the last Tsar and the room was primarily used for large receptions in the last years of the dynasty.

|

| Marble Drawing Room facing the Semi-Circular Hall |

|

| Mirrored door in the Billiard Room. |

|

| In the watercolor above, painted around 1860, we are looking away from the Semi-circular Hall toward a Karelian birch door which leads into the Palace Chapel. On either side of the door are large paintings. The one on the left, in a Gothic-style frame is of Queen Victoria by the artist Galter and was a gift from her to Nicholas I on his visit to England in 1844. The other painting is of Nicholas I's wife, Alexandra Fyodorovna by Neff. This painting was exhibited in the famous "Jewels of the Romanovs" exhibition which toured the USA in 1997. Looking carefully at this watercolor, four small oils lamps can be seen mounted on either side of the paintings. |

|

| A portrait in a Gothic-style frame is of Queen Victoria by the artist Halter and was a gift from her to Nicholas I on his visit to England in 1844. |

|

| The other painting is of Nicholas I's wife, Alexandra Fyodorovna by Neff. This painting was exhibited in the famous "Jewels of the Romanovs" exhibition which toured the USA in 1997. Looking carefully at this watercolor, four small oils lamps can be seen mounted on either side of the paintings. |

|

| Standing at the arch in the Marble Drawing room facing the Semi-circle Hall |

|

| Standing in the Marble Drawing Room facing the doors to the Palace Chapel |

|

| Sitting area in the Marble Drawing Room |

|

| Corner Mantle in the Marble Drawing Room |

|

| The Marble Drawing Room in 1917 |

The Palace Chapel

The Palace Chapel was established by Alexandra , and it replaced a sitting room of Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander II. Alexandra's ill-health made it difficult for her to go outside of the palace to the local church. Until the construction of the Fyodorovskii Sobor in 1912, which was on a secluded part of the Palace grounds, none of the local churches felt like 'home' to Alexandra. In Tsarskoe Selo there was the great Catherine Cathedral, but it was the chief cathedral of the town and always full of worshippers. Alexandra hated to be gawked at, particularly when she was praying, so she avoided visiting the town's churches until off-hours when there were few people about.

The Orthodox liturgy was very important to Alexandra and she tried to hear it as often as possible. She insisted her children attend frequently, as well. For convenience's sake the Palace chapel was indispensable and frequently used. In the picture above an ikonostasis that belonged to Alexander I can be seen crossing the center of the chapel. This screen followed the Emperor from Russia to Paris and back as part of the furnishing of Alexander's travelling camp church. The ikonostasis is now in the Menshikov Palace.

During services in the chapel the Imperial Family entered from the Billiard Room after servants and courtiers had already assembled in order according to their position with the highest closest to the altar on the right side of the ikonostasis. The Romanovs sat behind the glass screen shown above.

During their six month captivity after the revolution in the Alexander Palace the Romanovs had services as often as possible in the chapel. They weren't allowed to visit the Fyodorovskii Sobor or any other local churches, so the Chapel and Alexandra's small bedroom oratory where the only places for the religious observances that were so important to the family. Priests from local churches and members of the famous Imperial Choir came to the palace to perform the liturgy. In former days these services were packed with courtiers, servants and the nobility, but after the revolution thing were quite different. Although there were plenty of soldiers and guards outside the palace, within there were only a few to be seen. Services were now attended by two dozen or so people - servants, palace officials, a few friends and the family. Just beyond the walls of the chapel revolution and chaos reigned, but within life went on as it had for generations. The solemn chant of the Orthodox service, clouds of sweet incense, clergy and choristers dressed in splendid vestments of gold, silver, silk and damask - the atmosphere of Old Russia made the turbulent events outside seem like a bad dream.

_________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Dining Room (by architect Roman Meltzer, 1902) |

The Blue Boudoir

This room was built in 1844-45 and replaced the former Working Office of Alexander I. Quarenghi intended this quiet and secluded part of the palace to be the original private Imperial apartments and it was here that Alexander I and his wife Elizabeth lived when they used the palace during the first years of its existence.

The Blue Boudoir was first used by Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander II, who made the Alexander Palace her primary home. Late in her life she spent as much time as possible here in Tsarskoe Selo in seclusion from public life. For a number of years the Empress had endured her husband's scandalous affair with his young ward Catherine Dolgorukaya. Catherine's rooms were placed near her own in the Winter Palace, where she could hear her husband's bastard children playing one floor below her. This incredible lack of sensitivity on the part of her husband was one more reason she preferred being away from him in Tsarskoe Selo. Later this room was Maria and Alexander's formal reception room. It the style of the day it was decorated with furniture from many periods. The last furniture added to the room was in the Louis XVI style. It was delivered by the furniture maker Vidov in 1882.

In 1845 iron picture rails were erected throughout the palace and canvases rehung from them. The paintings here are by the famous Russian seascape painter Aivazovskii and other 19th century artists.

Maria Fyodorovna Bedroom

Maria Fyodorovna loved Tsarskoe Selo, while her husband Alexander III preferred Gatchina. The Imperial couple was expected to spend a part of the social season here in Tsarskoe Selo. Alexander found the parties and balls of Tsarskoe Selo a burden, but he bore them in gruding silence to humor his wife - she loved the relatively casual and elegant social life here. The Alexander Palace was the traditional home of the heir to the throne in Tsarskoe Selo and it was the home of Nicholas I, followed by Alexander II, then his son Alexander III. Nicholas II and his brother George were born in this room. Nicholas II spent his first night with his new wife, Alexandra, in this room. The wife of Nicholas I, Alexandra, died here on October 19, 1865.

These rooms were very similar to other rooms of the 1840's in other palaces and have walls covered with chintz which matches curtains and upholstery, creating an overall effect of plushness and uniform color. The room was redecorated a number of times in the 19th century. The room as we see it here is basically the work of the architect Stackenschnieder in 1845.

After the death of Alexander III this room - and all of the other his and his wife's other rooms, were frozen in time. The only change to the rooms were paintings taken away to become the nucleus of the Alexander III Museum in St. Petersburg, now known as the Russian Museum. This part of the palace turned into a kind of museum to Nicholas' parents and was carefully cleaned and kept in tip-top condition by palace servants. After the revolution these rooms were opened as part of the Alexander Palace Museum. They were taken over by the Secret Police as a private resort in the early 1930's.

Alexander III's Study

Alexander III had his office here when he was Tsarevich and used the room extensively throughout the 1870's. It had originally been a sitting room of Olga Nicholeavna, daughter of Nicholas I. The rooms has many similarities to the study of Alexander's son, Nicholas II. The big divan is the most striking feature and it almost fills up one side of the rooms, just as in Nicholas II's study of the opposite side of the palace. Alexander III was an amateur restorer of old paintings and a collector of fine art. He did much of his restoration work here in this room.

One striking difference between Alexander's study and that of his son is a large conference table here. Nicholas had no such table in his working study as he preferred to work with his ministers one-on-one.

_________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. Red and “Crimson” Drawing Room |

|

| A tiny model of the Alexander Palace, by Peter Carl Fabergé |

No comments:

Post a Comment